“Once you’ve set down the population centers, you can begin placing the Ruins locations. These Ruins represent lost cities, crumbled fortresses, stygian dungeon, plundered temples, abandoned towers of wizardry, and all the other decaying locales so beloved of adventurers.”

--An Echo Resounding: A Sourcebook for Lordship and War

Kevin Crawford (2012)

Step 11: Add Ruins

In our last installment, we added two major cities to our random map as well as a handful of towns. Now we’re going to place some potential adventure locations in the form of what Crawford calls “Ruins.” The book suggests the following:

- 5 ruins for every City.

- 1-3 of those were once major human cities, towns, etc.

- The rest can be whatever (wizards' towers, lost temples, ancient ruins, etc.)

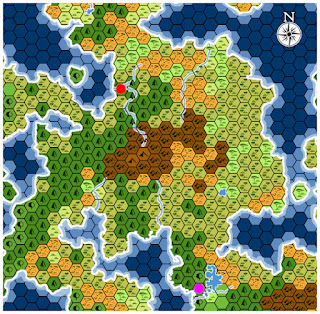

Since we placed 2 Cities in a previous step, we need to place about 10 Ruins. According to Echoes, 2-6 of these should be former human settlements of some kind. I’m trying to lean into randomness whenever possible and let the dice decide these sorts of things for me. So, I roll 1d6 and get a 6. Let’s represent those 6 ruins with some bright pink dots.

The remaining 4 ruins are the miscellaneous type referenced above. These we’ll note with bright yellow dots.

At this point, I still don’t know what these “ruins” represent, exactly. I’m not going to replace them with new symbols just yet. Until I know their nature, I don’t know if they’ll warrant a prominent map feature or just a note. For now, I’ll leave them as dots on a separate lair in my GIMP image file.

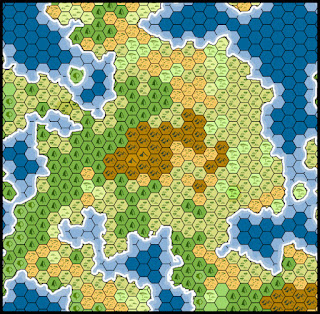

Step 11.5: Add a Map Grid

If I’m going to add features to the map that won’t necessarily get their own symbols, then I’ll need a way to keep track of where I put those features. Before I go too much further, I think I’ll add a quick and dirty grid labeling system to my map.

Now, a lot of old school maps put the grid labels right on the hexes themselves. I personally don’t care for that, as it makes things too cluttered and hinders the visibility, and therefore the usefulness, of the map itself. Instead, I’ll just label the rows and columns. Given the nature of the hex map, the row labels won’t match up perfectly. That’s fine. An approximation will be okay for our purposes.

Take a look at the map above to see what I mean. The area I’ve circled in pink is between two of the row labels. It could be expressed as E1 or E2. When mapping locations, if a hex falls between the labeled rows like this, I’m going to choose the northmost row. In this case, that makes this hex E2. It’s not completely precise, but it will work well enough for our purposes

Step 12: Add Lairs

In An Echo Resounding, the next step is technically “establish resources”. That step is tied-in with the author’s realm management system, which we’re not really going to worry about for this exercise. Instead, we’re going to skip right to “placing Lairs.”

Lairs are sort of reverse-towns. They are the havens for the monsters, bandits, and other hostiles in the area, and inherently hostile to player characters. To use the old school paradigm of D&D adventure progression, Ruins are for Dungeon exploration and Lairs represent Wilderness play.

For Lairs, I'm using gray squares. Adding them according to the advice in Echo, here's what the end result.

Next Time

We'll take a break for the mapping in order to make some decisions about the campaign itself.